| October 10, 2023

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

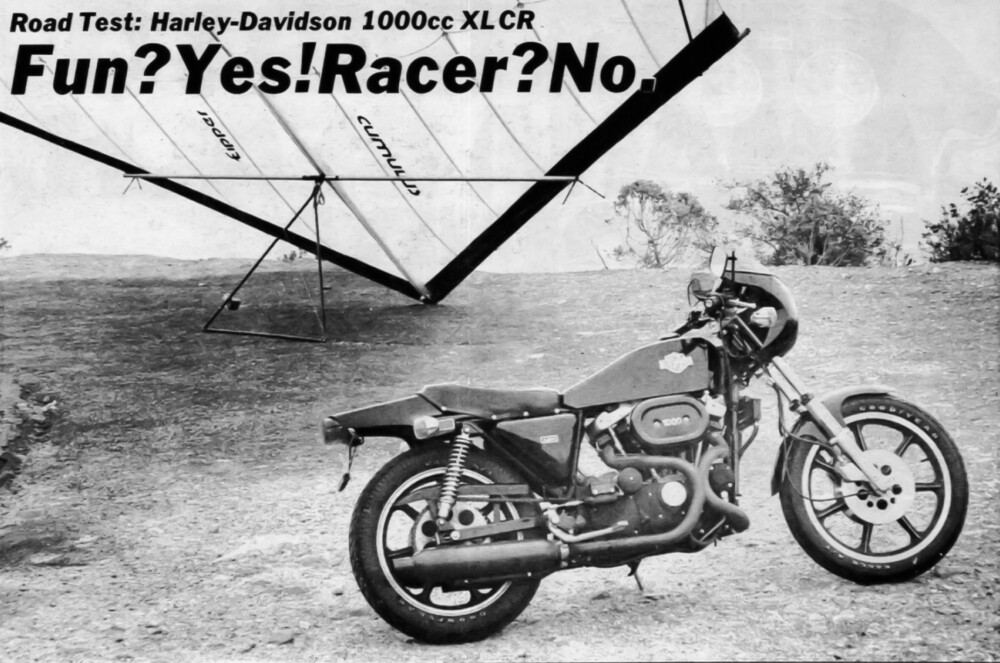

The Racer That Wasn’t

By Kent Taylor

It was an oft-seen Saturday afternoon television commercial in the early 1970s. As the average American sat in a comfy chair, watching hour after hour of sports programming, the ad with the happy cartoon characters encouraged them to get up, get their products and get moving. “We make VOIT basketballs,” the spokesperson stated. “Head tennis racquets. Ben Hogan golf equipment. Harley-Davidson motorcycles.”

The 1978 Harley-Davidson XLCR was the company’s first and last attempt at producing a café racer-style motorcycle. It lasted just three years.

The 1978 Harley-Davidson XLCR was the company’s first and last attempt at producing a café racer-style motorcycle. It lasted just three years.

Harley-Davidson motorcycles? One of these things (cue the Sesame Street jingle) is not like the others!

“We make,” said the voice from the television, “weekends!”

The highly diversified “we” in the television commercial was the American Machine and Foundry, better known as AMF, a company created in 1900 by Rufus Patterson, a high school dropout who went on to become a mechanical engineer. One of his most successful inventions was the “Patterson Packer,” which seemed to be something of a do-it-all machine in the field of cigarette manufacture.

Rufus had been gone many years when AMF acquired the Harley-Davidson brand in 1969. While H-D faithful have few positive opinions about the AMF years, it is poppycock to say that they weren’t trying to build their customer base, imploring folks to get off the couch and onto a V twin! And in 1977, AMF reached out to a market that even the Big Four hadn’t considered with their very first (and only) cafe racer, the Harley-Davidson XLCR.

It is ironic, to say the least, that Harley-Davidson was the only major manufacturer offering a cafe racer-style motorcycle in its official lineup. America would see the birth and blissful death of disco music before sport bikes would begin dominating the showrooms of motorcycle dealerships across the country.

Cycle News’ staffer John Ulrich tested the XLCR for the January 25, 1978, issue. How did he feel about Harley-Davidson’s bold leap into the future, releasing its 500-pound iron lunged machine to the world? It would be a significant understatement to say that he was underwhelmed.

“Wonder of wonders,” he stated. “The bikes starts quickly and moves off instantly…”

Once the initial combustion has taken place, however, the test begins a steady descent into motorcycle hell:

- It takes a long foot to shift the XLCR…

- The racing seat (is) a piece of foam and a snapped-on vinyl cover.

- The small headlight does a better job of spotting the bike for other traffic than of lighting the rider’s way.

- The horn button isn’t where it is on other bikes.

And there is the inevitable reference to the Harley-Davidson shake. “Of course, the engine vibrates,” the tester states. “It trembles the handlebars, footpegs, seat and mirrors at every rpm, at every speed. It’s always there…”

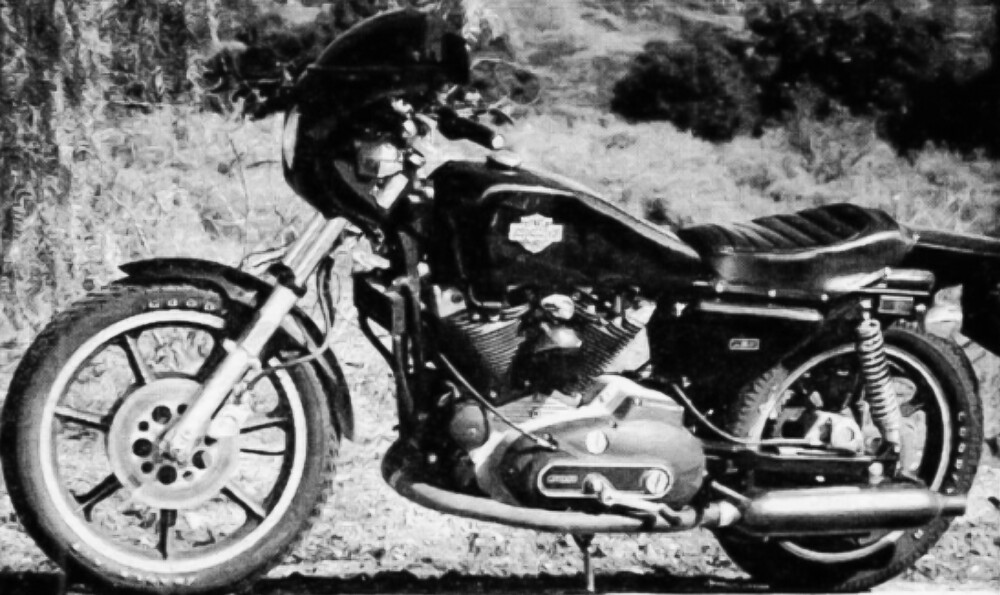

The H-D XLCR Café Racer was built during the Harley AMF era.

The H-D XLCR Café Racer was built during the Harley AMF era.

It became clear that the XLCR wasn’t really a cafe racer. The suspension, both front and rear, wasn’t up to the task of hard cornering. And the brakes? Ulrich wrote, “…they have no predictability, no feel, no warning…there is no middle ground.”

And that was while riding the motorcycle in dry, optimal conditions. Braking when wet was a foolhardy endeavor; fortunately, the bike’s considerable engine braking was enough to “almost make the XLCR stop.”

If the XLCR wasn’t a cafe racer, then what was it? A touring bike? Wrong again! The XLCR was so uncomfortable that anything more than a 30-minute ride was akin to a pleasurable half-hour on a medieval rack. Its rear-set pegs may have made sense on the drawing board, but on the road, they put the rider in an uncomfortable crouching position (though, in all fairness to H-D, street riders were unaccustomed to sport bike riding in 1978). And the tiny windshield on the top of the fairing sent a blast of wind “right up the rider’s nose.”

Perhaps the only way to truly enjoy the XLCR required the rider to confront these deficiencies head-on—and then forget about them! Treat it as you would your child. Embrace the vibration, taking it in like the heartbeat of your firstborn. Smile as it struggles to compete with the faster kids. Sometimes, it will make you feel uncomfortable, and it won’t listen to you when you tell it to stop, but you will love it for what it is: an unashamedly loud, underperforming Harley-Davidson.

“Fun,” said Ulrich. “That’s the word to remember. Because if you get serious, put on a race face, and try to chase a good rider on anything nimble, then you’ll risk “face” at best and “life” at worst.

Production of the big, black $3500 beast would cease after just three years. Just 3200 XLCR’s were manufactured.

In 1981, H-D executives teamed up to buy their way out from under the reigns of AMF; a couple of years later, the Reagan administration gave the Motor Company a leg up on the competition, slapping a $500 tariff on all Japanese motorcycles over 750cc (thus, giving birth to a new class of 700cc motorcycles from Japan).

And the XLCR? In 2022, a clean model with 31,000 miles on the clock netted $15,500 at auction, perhaps finally giving definition to the oddball Harley: if nothing else, it was a good investment! CN