Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

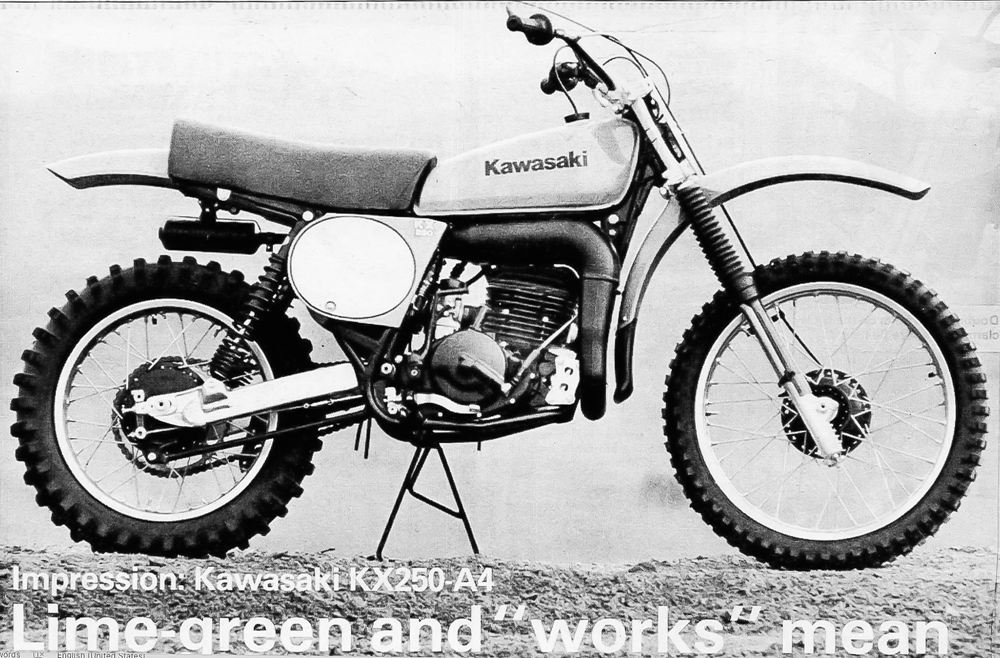

A works bike you could buy?

By Kent Taylor

In the 1970s world of professional motocross, deep and wide was the chasm between the pampered life of the factory-sponsored racer and the buzzing pack of self-supported wannabes. Exotic, finely tuned instruments known as works bikes served as steeds for the haves, while the have-nots plodded along with machinery that looked like it had just been rolled off the showroom floor because, well, they had just been rolled off the showroom floor. While the hand-built exotica were reserved for the princes of the sport, the stock bikes were mass-produced for the plebeians, accessible to all who could scrape together enough bones for the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

All except one, that is. The 1978 Kawasaki 250 A4 was made in a limited production run. Here was a motocross machine that its manufacturer dared to call a real works bike. Was it a real works’ motorcycle? The answer was “yes!” Why? Because Kawasaki said it was!

In February of 1978, Cycle News tested the all-new Green Machine at the famous Saddleback Park motocross track. California’s winter season brought rain that transformed the hard-packed course into a gooey cake batter. A rare occurrence, to be sure, but what was particularly unusual about the day was that Kawasaki USA had sent along “a chaperone” for its replica racer!

“It’s a full-on, works replica, and it needs to be maintained like one,” said Kawasaki’s PR man Jeff Shetler. Shetler would keep a watchful eye on the A4, which was delivered to the track that morning and would be returned to company headquarters that same evening, making the experience more of an impression than a thorough evaluation, and the Cycle News staff was right-minded and noble in labeling it as such. So, what kind of an impression did this self-proclaimed works bike make on the CN staff?

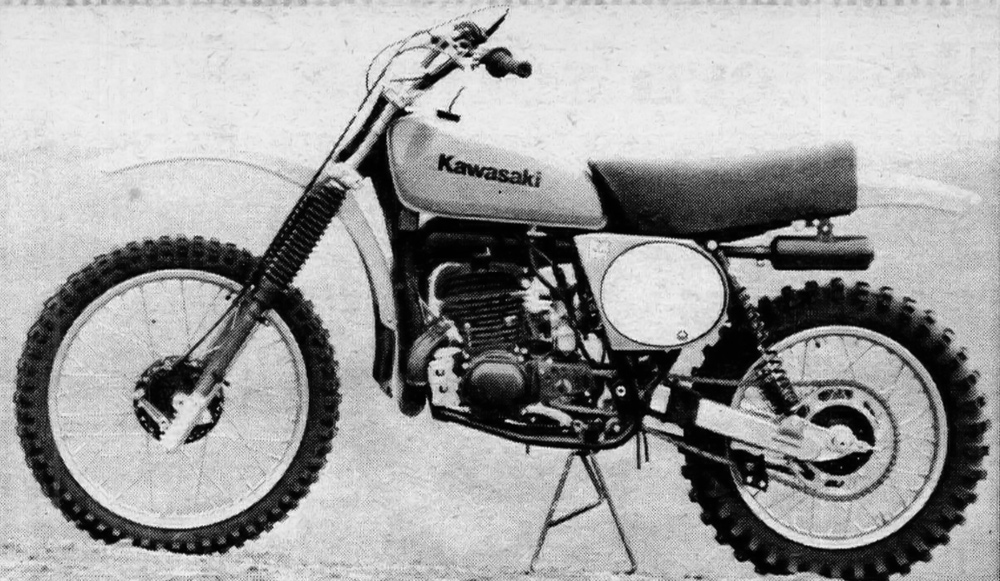

“Lime green and works mean,” read the headline, and the A4 was eye candy from the get-go. The eye was drawn to the gold anodized, aluminum swingarm, which was a rarity for a production motorcycle in the 1970s. The fork was an air/oil adjustable unit from Kayaba, the company which also provided springers for the rear end. Those shocks were connected to a swingarm that rolled on needle bearings versus the more conventional bushings found in the Kawasaki’s competition. Needle bearings arguably provided a smoother pivot point but also required more maintenance. But ownership of a works bike brings with it a much more involved maintenance schedule, so no A4 owner should’ve been surprised by the frequent teardown for inspection and cleaning of the needle bearings.

Strategic use of lightweight metals, like aluminum and magnesium, helped the A4 keep its girlish figure, tipping the scales at a claimed weight of just 207 pounds. A generous use of lightweight metals won’t even bring a second glance from 21st century MX bike shoppers, but again, this was 1978, and the Kawasaki stood apart from the competition in its makeup.

But the real test of a motocross bike has nothing to do with good looks or even lightweight. On the track, the A4 proved to be a solid machine. Tester Dave “Keep It Sano With Miller Mano” Miller put the green bike to work on the muddy track and found it to most certainly be an expert-only machine. “If the Kawasaki comes out short in any way,” said CN, “…it won’t be due to insufficient power, at least not on the top end.”

Miller had more compliments for the “works” bike. “The clutch is perfect…I can use it with one finger!” Stopping the bike was easy because “the brakes are perfect.” And the many magnesium and aluminum components meant that “this baby is light…no vibration, either.”

But could the A4 live up to its works moniker when put to the test by a top pro rider, one who was more accustomed to such exotic machinery? In the summer of 1978, MX’er Billy Grossi agreed to a short-term stint for Terry Dorsch, a longtime dirt track star who had become a Kawasaki dealer in Santa Cruz near Grossi’s home. Grossi, a former member of Team Kawasaki, Honda, Suzuki and just about every other brand, piloted one of Dorsch’s A4s in a local Northern California summer series. He found the Kawasaki to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing.

“It had a works bike look and was pretty light, but that’s where the ‘works’ part ended,” Grossi remembers. “I recall it having a light-switch powerband and very twitchy handling. The short wheelbase and harsh suspension made it quite a handful on the technical tracks in our area. I probably only raced this bike four to five times locally, winning a few motos but it also had a habit of pitching me to the ground more often than not! It looked good on the bike stand, but unfortunately, I did not get along with this Kawi.”

Kawasaki was not the choice of rides for the privateer pro racer at the time. A look at results in the mid-to-late ’70s would reveal that most of the top non-factory riders were aboard Maicos, Husqvarnas, Hondas, Suzukis, Yamahas, etc. Almost everything but Kawasaki, so it was understandable that the company was hoping that the new 250 would change that. A limited number of just 2000 bikes would come into the U.S. and according to Cycle News, dealers were encouraged to “see fit to sponsor a good local rider” who might also take his new A4 to the nationals and demonstrate that this truly was a works bike for the working man.

Scanning the results of the 1978 AMA 250cc National Championship series reveals a handful of top 20 finishes from privateer Kawasaki riders Charles Cooper and Steve Bauer, who said, “The suspension was behind the times, but they came out with the Uni-Trak a year later. Kawasaki gave me one [the A4] to race, but I liked my Honda better. I raced the Kawi a few times and even won on it but eventually gave it back.” A year before, in 1977, that number was zero; no one rode a Kawasaki, so while the green company hadn’t produced a true works bike for the masses, with the A4, they clearly had taken a significant step toward making Kawasaki a more viable competitor. CN

Click here to read the Archives Column in the Cycle News Digital Edition Magazine.

Subscribe to nearly 50 years of Cycle News Archive issues