| May 22, 2022

Cycle News Archives

COLUMN

The Man Behind the MX Face Mask

By Martina Faltova Cope, with Kent Taylor

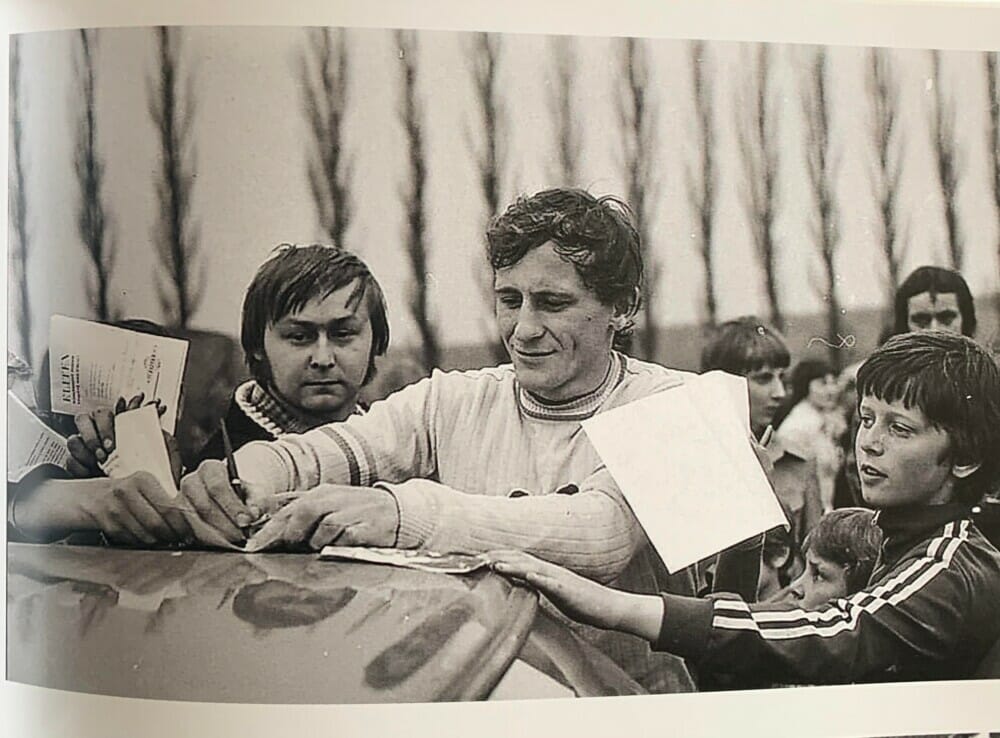

To motocross fans, Jaroslav Falta was a famous rider of CZ motorcycles. He was a fierce competitor who won races around the world, including the Super Bowl of Motocross in California in 1974. He was also the man who should’ve been the 250cc Motocross World Champion that year as well, losing it only for reasons that had nothing to do with racing and everything to do with politics.

Jaroslav Falta passed away earlier this year.

Jaroslav Falta passed away earlier this year.

This is how you know Jaroslav Falta. But I would like for you to become acquainted with the man behind the motocross face mask. My name is Martina Faltova Cope and the man that you knew as a champion motocross rider was also the man that I called “táta” or “Daddy.” Jaroslav Falta was my father. Like all relationships, we had our ups and downs (a lot of downs in my teens!), but he was a wonderful father to me and my brother, Jaroslav Jr. Now that he is gone, I want all to know him as something more than just a man who could go fast on a motorcycle. He was a shy man, so I am sure he would be more than just a little embarrassed by the following story about my beloved “táta.”

I have known of many retired motocross champions in the United States and around the world. Many of them have taken their motocross earnings, invested those funds in successful businesses and are living comfortable lives. Living in Communist Czechoslovakia back then, something like this was just not possible. Even though he won many races and had a very successful venture into American racing, the Czechoslovakian government allowed him to keep only a portion of his winnings. My father told me that in 1974, he won more than $25,000 in prize money during the summer alone when he won the 1974 Inter Am Series and, of course, the Super Bowl of Motocross in the United States. That would be nearly $150,000 in today’s economy. The Communist government, however, put a heavy tax on his winnings, which left him with very little to show for his victories. He took the small amount that he was allowed to keep and used it to help build our family house.

Falta was a hero in his native Czechoslovakia.

Falta was a hero in his native Czechoslovakia.

Nor did he become wealthy from his Grand Prix racing, where he was paid about $5 per point he scored. In the 1970’s, a moto win was worth 15 points, so even if he would win both motos on the day, he would be paid about $150. Because he had known only motocross for so long, employers thought he did not have other skills, so when his racing days were over, my father went to work as a security guard at the Smer Toy factory. You can certainly imagine how great a change this was for him. He had traveled the world, competing against the best riders. His name and photos were in all of the motorcycle magazines. Crowds cheered for Jaroslav Falta, beautiful trophy girls gave him kisses and champagne. And then one day, it was all over, and he was working the graveyard shift at a factory where they made plastic toys. It was a sudden and huge difference in lifestyle, routine and life purpose. My father would experience depression and some hard times over the next 10 years. Somehow, he was still able to provide a comfortable life for all of us.

But I can tell you that the events of 1974 hurt him deeply. The story has been told many times; what the Russian (at that time Soviet Union) motocross team could not do on the track, they succeeded in doing off it. Jaroslav Falta may have been the fastest motocross racer in the world in 1974 and that is something I say not because I am biased toward my father. He defeated the best American riders on their own soil that year. In the Super Bowl, he beat all of them again—and Roger DeCoster, too. It should be noted that event was his first (and only) attempt to ride stadium motocross. There are photos of him, beaming on the victory podium in Los Angeles; there is nothing in this world more beautiful than a genuine smile on a humble man’s face.

Sadly, it would be just a few weeks later in Wohlen, Switzerland where my father would experience both the best and worst days of his motocross career. On that day, he won the 250cc World Championship on the racetrack, only to lose it to a bullying Russian team and backstage FIM politics. His only chance to reclaim what was rightfully his would come later at the FIM conference when the Wohlen issue was debated. Sadly, his own countrymen failed him that day, as well.

My father was heartbroken. He had won it, fair and square, but was ordered by our government not to talk about it. It was no idle threat; they had the power to keep him from ever racing again, so he had to make up stories about what happened. It was easiest to simply change the subject every time the incident at Wohlen would come up.

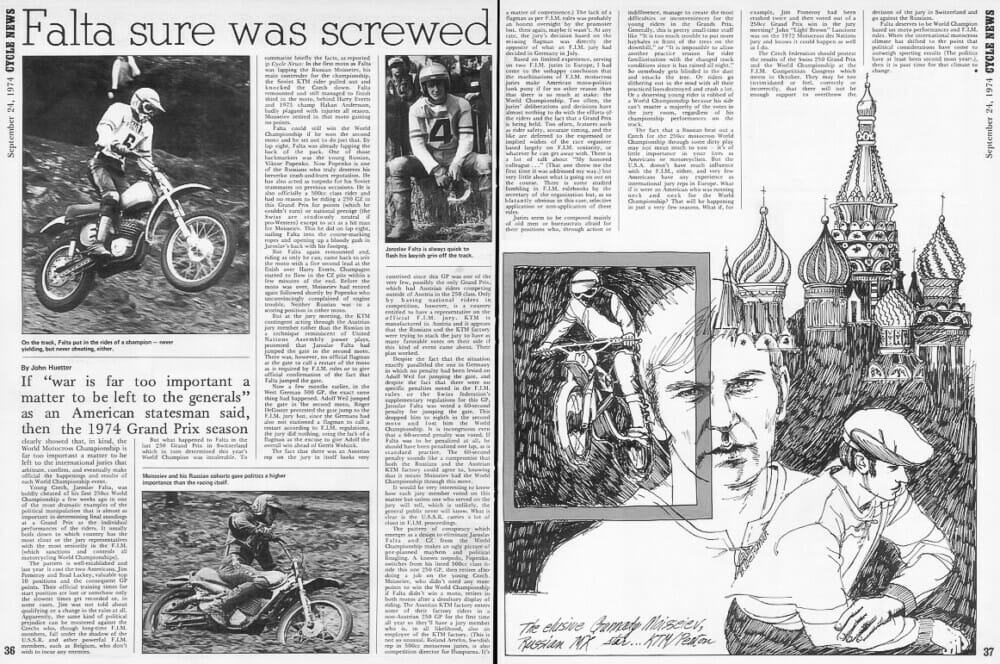

Our headline 48 years ago says it all.

Our headline 48 years ago says it all.

In 1975, Dad was determined to win that championship. He was victorious at the Austrian Grand Prix early in the season and was contending for the title when he became very ill with a blood disorder. It very nearly took his life. My father was a strong man and while he defeated the disease, he would miss the rest of that season. He would return to racing and would win again but by the late 1970s, CZ motorcycles were no longer competitive at the world championship level. I am certain he looked longingly at the sophisticated Japanese machines, but he was not allowed to ride a motorcycle made anywhere other than Czechoslovakia. He retired from racing in in 1984, leaving it behind him. My father gave up riding completely. There would be no more motorcycles and he did not follow the sport in any way. It was in his past, that was where he wanted it to remain and we did not speak of motocross for many years.

You might assume that he was bitter and angry. If that is true, then only he knew about it. My father was a very quiet man and believed that his actions spoke more loudly than any words he could ever use. He also never raised his voice. Never did I hear my parents argue, simply because it never happened. He was not perfect, and he was no angel, but he did not like confrontations. My mother would talk about the problem and if there was something in the “talk” that he could fix, it was fixed the next day.

And speaking of fixing, my Dad loved to repair things! There was nothing he could not fix. He never threw anything away! Sometimes, he would bring something home and we would ask him “why did you bring this crap home?” “You never know,” he would respond. “Maybe one day you or your brother will need it.”

While Jaroslav Falta may have tried to forget motocross, motocross’ fans would not forget him! In 1997, Ivo Helikar (the son of my father’s coach) and I wrote a book about my father’s career. It was called “Ukradený titul,” which translates to “Stolen Title.” For the first time in years, he began to open up and share some feelings about his racing. Still, he was often unable to speak comfortably about the 1974 incident. We would do book tours and many interviews, but when the conversation turned to Wohlen and the Swiss Grand Prix, my father would get tears in his eyes, and he could not answer the questions.

It was not until the last few years of his life that he would return to coaching and riding. He began making trips around the world to ride in vintage events, some of them for CZ riders only. Along with his old friend and CZ teammate Zdenek Velky, Dad traveled to the United States for the CZ World Championships as a guest of honor. He was often introduced as the “real” 1974 250cc World Champion! He was overwhelmed by the attention he received from these race fans. I set up a Facebook page for him and he would scroll through, read the many affectionate comments, and just shake his head in disbelief. He had no idea how greatly he was loved. Ironically, the fact that he did not win the title seemed to make him something even greater than a champion for MX fans around the world.

He slowly began to embrace motorcycles and his beloved sport of motocross once again. He even began coaching young riders here in the Czech Republic. This year, my mother and father were planning a special trip—to Switzerland! He even planned to return once again to the city of Wohlen. Perhaps the healing process had begun!

I called my father on March 22, which was his 71st birthday. He was in a great mood—working in his shop and fixing something. We didn’t phone each other often, so when my mother called me again just five days later, I knew immediately that something was wrong. My mother said he hadn’t been feeling well that day. Initially, they had attributed it to an old spine injury suffered in a motorcycle accident in 2007. He had learned to live with a lot of pain; some days, he simply just needed to rest, which is what he was doing that day. But when he said he was struggling to breathe, my mother called for the ambulance.

The man who defeated the world’s best riders on the racetrack, who would later overcome a life-threatening blood disease and a nearly paralyzing back injury, would not go gently from this world. He was revived twice, before finally, resting in my mother’s arms, the man who I loved and adored more than any words can say was gone.

His funeral was held at the largest funeral hall in our country. Friends came in on buses and airplanes to honor my father. His former teammates, some of them now needing the help of walkers and crutches, stood guard at his casket. His friend Zdenek Velky told everyone, “as much as we raced and fought on the track, that much we also loved each other. We were at each other weddings as best men—and now we are here.”

The pathology report showed something that we had long suspected: my father had a large heart—one-third larger than that of a normal human being! It did not contribute to his death; in fact, I like to think that his special heart helped make him the special man that he was, to both you and me.

As I mentioned, my father was famous for bringing home things that we thought were not necessary. “Maybe one day,” he said, “you will need it.” I now know that one of those things that he brought into my life was his courage. Tata, you are right—I do need it, now more than ever before.

Stolen Title, the story about Jaroslav Falta’s life and career will be published in English in the fall of 2022… ~Editor