Cycle News Staff | May 4, 2020

After learning that Motocross legend Marty Smith and his wife passed away in a dune buggy accident last week, we dug through the Cycle News Archives to pull together info for a feature in this week’s issue. One of the stories we found was an interview that Eric Johnson wrote for Cycle News in March 1997. The interview focuses on 1976, the year that Smith raced both the AMA 125 Nationals and FIM 125 World MX championship. Read on to learn more about Smith’s recollection more than 20 years later. You can read the original file here.

By Eric Johnson

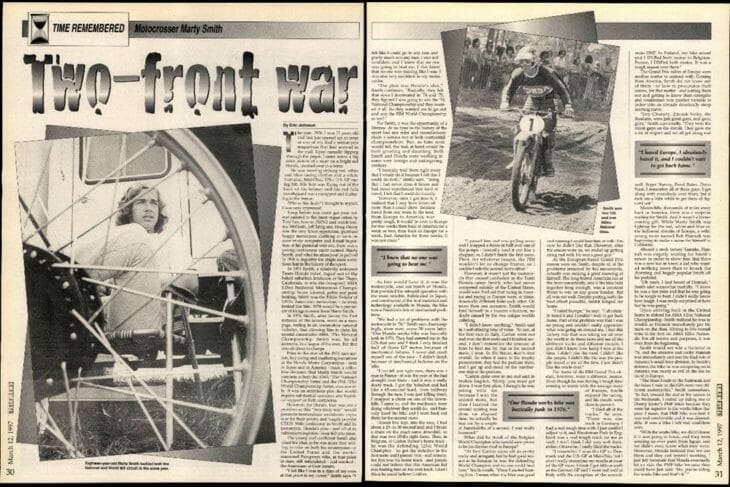

The year: 1976. I was 12 years old and had just opened up an issue of one of my dad’s motorcycle magazines that had arrived in the mail. Upon casually flipping through the pages, I came across a big color picture of a racer on a bright red Honda, cranked over in a berm.

He was wearing striking red, white and blue racing clothes and a white Valvoline, Mid-Ohio, 125cc U.S. GP racing bib. His hair was flying out of the back of his helmet and his red Jofa mouthguard was unsnapped and fluttering in the breeze.

Who is this dude? I thought to myself. I was very impressed.

Eric Johnson conducted this interview with Marty Smith in 1997. Smith recounts the 1976 season when he raced both the AMA and FIM championships.

Eric Johnson conducted this interview with Marty Smith in 1997. Smith recounts the 1976 season when he raced both the AMA and FIM championships.

Long before you could get your helmet painted in the latest vogue colors by Troy Lee, tune in ESPN2 and watch Jeremy McGrath, Jeff Emig and Doug Henry win the very latest supercross, purchase baggy motocross clothing or turn on your trusty computer and E-mail Supermac at his personal web site, there was a young motocross racer named Marty Smith, and what he attempted to pull off in 1976 is arguably the single most ambitious feat in the history of the sport.

In 1974 Smith, a relatively unknown Team Honda rider, raged out of the baked suburban landscape of San Diego, California, to win the inaugural AMA 125cc National Motocross Championship. Super talented, polite and good looking, Smith was the Eddie Vedder of 1970s American motocross – he even looked like him.1974 would be a precursor of things to come from Marty Smith.

In 1975 Smith, after losing the first national of the season, went on a rampage, reeling in six consecutive national victories, thus allowing him to claim his second consecutive AMA 125cc National Championship. Smith was, by all accounts, in a league of his own. But that was all about to change.

Prior to the start of the 1976 race season, key racing and marketing executives at the Honda Motor Corporation – both in Japan and in America – made a collective decision that Marty Smith would compete in both the AMA 125cc National Championship Series and the FIM 125cc World Championship Series, concurrently. It was an ambitious plot that would. require substantial resources and logistical support on both continents.

However, for Honda, that was not a problem as this “two-front war” would generate tremendous worldwide exposure for their potent, and hugely popular CR125. With confidence in Smith and its motorcycle, Honda’s plan – and all of its subsequent logistics – soon fell into place. The young and confident Smith also liked the idea, as he was more than willing to take on both his countrymen in the United States and the world-renowned Europeans who, at that point in time, still intimidated – and smoked – the Americans at their leisure.

“I felt like I was in a class of my own at that point in my career,” Smith says. “I felt like I could go to any race and pretty much win any race. I was real confident and I knew that no one was going to beat me. I also knew that no one was training like I was. I was also very confident in my motorcycles.

“The plan was Honda’s idea,” Smith continues. “Basically, they felt that since I dominated in ’74 and ’75, they figured I was going to win the ’76 National Championship and they wanted it all. So they wanted me to go out and win the FIM World Championship as well.”

For Smith, it was the opportunity of a lifetime. At no time in the history of the sport had any rider and manufacturer made a serious run at both continental championships. But, as time soon would tell, the task at hand would be both grueling and daunting. Both Smith and Honda were working in some very foreign and unforgiving territory.

“I basically told them right away that I would do it because I felt that I could do both,” Smith says. “Being that I had never done it before and had never experienced that kind of travel, I felt that I could do it easily.

“However, once I got into it, I realized that I may have bitten off more than I. could chew. Because travel from one week to the next, from Europe to America, was pretty tough. It would be over to Europe for two weeks then back to America for a week or two, then back to Europe for a week, then America for three weeks; it was just crazy.”

As fate would have it, it was the motorcycle, and not Smith or Honda, that provided the intrepid operation with the most trouble. Fabricated in Japan and constructed of the best materials and technology available to Honda, the bike was a Pandora’s box of mechanical problems.

”We had a lot of problems with the motorcycle in ’76,” Smith says discouragingly, even now, some 20 years later. “Our Honda works bike was basically junk in 1976. They had entered me in the GPs that year and I think I only finished half of those GP motos because of mechanical failures. I never did crash myself out of the race – I didn’t finish because of mechanical failures on the bike.

“I can tell you right now, there was a race in France – it was the year of the bad drought over there – and it was a really dusty track. I got the holeshot and had like a 45-second lead, then halfway through the race, I was just killing them, I snapped a chain on one of the down hills. I came in, and the mechanics were doing whatever they could do, and basically fixed the bike and I went back out there for the second moto.

“About five laps into the race, I had about a 25- to 30-second lead and I broke a chain on the exact same downhill, so that was two DNFs right there. Then, in Belgium, at Gaston Rahier’s home track – he was the defending 125cc World Champion – he got the holeshot in the first moto and I passed him- and remember this was his home track – and people could not believe that this American kid was beating him on his own track. I don’t think he could believe it either.

“I passed him and was pulling away and I snapped a frame in half over one of the jumps – basically toed it out like a chopper, so I didn’t finish the first moto. Then, for whatever reason, the FIM wouldn’t let us change frames, so I couldn’t ride the second moto either.”

However, it wasn’t just the motorcycle that caused confusion in the Team Honda camp. Smith, who had never competed outside of the United States, would soon find out that racing in America and racing in Europe were, at times, drastically different from each other. On more than one occasion, Smith would find himself in a bizarre situation, no doubt caused by the two unique worlds colliding.

“I didn’t know anything,” Smith said in a self-effacing tone of voice. “In fact, at the first race in Italy, Gaston went out and won the first moto and I finished second. I don’t remember the amount of time he beat me by, but in the second moto, I won. In the States, that’s first overall. So when it came to the trophy presentation, they had the podium there, and I got up and stood on the number one step of the podium.

“Gaston came over to me and said in broken English, ‘Marty, you must get down. I won first place, I thought he was joking with me because I won the second moto, but then I learned the overall scoring was done on elapsed time. So, actually he beat me by a couple of hundredths f a second. I was really bummed.”

What did he think of the Belgian World Champion who would soon prove to be his fiercest rival in Europe?

“At first Gaston came off as pretty cocky and arrogant, but he had good reason to be because he was the defending World Champion and no one could beat him,” Smith recalls. “Once I started beating him – I mean when my bike was good and running I could beat him at will – I’m sure he didn’t like that. However, after the season wore on, we ended up getting along real well He was a good guy.”

As the European-based Grand Prix season wore on, Smith, despite all of the problems incurred by his motorcycle, actually was making a great showing of himself .The long-haired American ran at the front consistently, and if the bike held together long enough, was a constant threat to win on any given Sunday. But all was not well. Despite putting forth the best effort possible, Smith longed for home.

“I hated Europe,” he says. “I absolutely hated it and I couldn’t wait to got back home. Part of the problem was that I was so young and couldn’t really appreciate what was going on around me. I had this factory ride that was taking me all over the world to do these races and see all the different tracks and different circuits. I just didn’t know how lucky I was at the time. I didn’t like the food. I didn’t like the people. I didn’t like the way the people stared at me all the time. I just didn’t like the whole deal.”

The tracks of the FIM Grand Prix circuit, however, were a different matter. Even though he was having a tough time corning to terms with the strange ways of Europe, Smith enjoyed the racing, and his results were there to prove it.

“I liked all of the tracks,” he says. “There was one track in Germany I was really had a real tough time with. I just couldn’t adjust to it, and Hawkstone Park in England was a real tough track for me as I don’t think I did very well there. Otherwise, I really liked the tracks.

“I remember I won the GP in Denmark and the U.S. GP at Mid-Ohio; but I don’t really remember my results at most of the GP races. I think I got fifth or sixth at the German GP and I went real well in Italy with the exception of the second moto DNF. In Finland, my bike seized and I DNFed both motos in Belgium. France, I DNFed both motos. It was a tough season over there.”

The Grand Prix riders of Europe were another matter to contend with. Coming from America, Smith did not know any of them – or how to pronounce their names, for that matter – and sorting them out and getting to know their strengths and weaknesses was another variable to factor into an already drastically steep learning curve.

“Jizy Churavy, Zdenek Velky, the Russians, were just great guys, real great guys,” Smith says fondly. “They were the nicest guys on the circuit. They gave me a lot of respect and we all got along real well. Roger Harvey, Pavel Rulev, Dario Nani, I remember all of those guys. I got along with everybody over there, but it took me a little while to get them all figured out.”

Meanwhile, thousands of miles away back in America, there was a surprise waiting for Smith. And it wasn’t a home coming gift. While Marty Smith was fighting for the red, white and blue on the hallowed circuits of Europe, a wild, young racer named Bob Hannah was beginning to make a name for himself in California.

Aboard a stock factory Yamaha, Hannah was eagerly waiting for Smith’s return in order to show him that there was a new kid in town; a kid who wanted nothing more than to knock the charming and hugely popular Smith off his pedestal.

“Oh yeah, I had heard of Hannah,” Smith said somewhat ruefully. “I knew he was a fast rider and that he was going to be tough to beat; I didn’t really know how tough. I was really surprised at how fast he was going.”

Upon arriving back in the United States to defend his AMA 125cc National Championship, Smith realized he was in trouble as Hannah immediately put his mark on the class, blitzing to five overall wins in the first six AMA 125cc Nationals. For all intents and purposes, it was over from the beginning.

Smith would not win a National in ’76, and the abrasive and cocky Hannah was immediately cast into the lead role of America’s small-bore division. In Smith’s defense, the bike he was competing on in America was nearly as evil as the one he raced in Europe.

“The bikes I rode in the Nationals and the bikes I rode in the GPs were two different motorcycles,” Smith remembers. “In fact, toward the end of the season in the Nationals, I ended up riding one of Donny Emler’s FMF bikes because they were far superior to the works bikes that year. I mean, that FMF bike was fast! It was real comfortable and it was dependable. It was a bike I felt real confident with.

”With the works bike, we didn’t know if it was going to break, and they were sending us over parts from Japan, and we didn’t even know what they were. However, Honda insisted that we use them and they just weren’t working. I just felt fortunate that Honda eventually let us ride the FMF bike because they could have just said: ‘No, you’re riding the works bike and that’s it.”

However, despite those aggravating problems, Smith still put his best foot for ward and made the best of a somewhat lackluster year in the States. Even though the AMA season hadn’t gone the way he had hoped, Marty was still happy to be home – at least for the time being.

“The Nationals meant more to me because that’s where all my fans were,” Smith says in retrospect. “In Europe I didn’t have that many fans. In fact, I think most of the people over there didn’t like me because I was beating their guys. At the Nationals, after winning the championship two years in a row, I had a lot of fan support.

“It was just being back in America, as well. You know the lingo, you know the food, you know the tracks – some of them we would see two or three times a year – and you know all of the people. Then you go to Europe and you don’t know anybody and don’t like the food, you don’t speak the language. There is just no comparing the two places.

“It didn’t affect how I rode. I still rode real well because I actually ended up third overall in the GPs. At that time, it was the best an American had ever done over there. I could have won the thing if it wasn’t for all of the mechanical failures. The jet lag didn’t really bother me at all.”

While there were numerous problems, challenges and disappointments for Smith in both Europe and America, the year 1976 certainly held some very bright moments for the San Diego native. In fact, I vividly remember seeing a picture of Smith immediately after the Grand Prix of Denmark

Within the picture, a weary, but happy Smith is sitting in a lawn chair – certainly brought from back home – a pretty blonde girl is sitting in his lap, he has a victory wreath around his neck, a number of Japanese and American technicians are standing around him, he is drinking a bottle of champagne and he is smiling big. Does Marty Smith remember that moment?

“(Laughter) Yeah, right, I do remember, and that’s my wife. You know what, I probably didn’t sleep well the night before. A lot of the time the food was crappy, we were staying at all of these hotels in different countries and a lot of times we did a lot of driving, as well. We drove to each country, we didn’t fly.

“I remember we had a rental car and the big race- truck van and we just drove from country to country, through all of these border lines and a lot of times we would get hung up in customs and we would have to give the guards a bunch of stickers and T-shirts or something just to get through. Still, that was a great memory.”

What about the aforementioned picture of the 1976 Mid-Ohio United States Grand Prix, where despite the ups and downs of the season, he took the measure of Bob “Hurricane” Hannah?

“Oh yeah, it was great, Smith recalls very fondly. “It was a good race for me. I know that my United States bike was better than my European bike. [ know that I could win both motos because I had won both motos, with holeshots, the year before in ’75. In ’76, I did the same thing. I remember Hannah was behind me in moto one and was dogging me hard, pushing me. I remember once I brakechecked him and it dropped him back like five seconds. I don’t know if he stalled or tipped over, or what. I won again in the second moto, as well.

“The bottom line was that I got both holeshots and won both motos that day. It felt good because I beat Hannah, who was the new kid then. You know a lot of people say that Hannah was faster than me that year, and Bob was a very good rider then, but he had a far superior bike with that OW20 Yamaha. That bike was superior, it was really good. I could have beat him with my bike that season, but it just wasn’t my year.”

While the year 1976 will long be remembered for the potent rivalry between Marty Smith and Bob Hannah, it appears that the struggle was more a figment of people’s – and journalists’ – imagination than any real bad blood between the two.

Smith explains: “You know, there was always razing about Hannah. Everybody thought that we hated each other, and it probably looked like it out on the track, but who has friends on the track? Nobody does. We actually got along real well. On the starting line, or in the pits, at the hotel, or in restaurants, we got along just fine.

“That whole myth that we hated each other was done by the riders, It didn’t bother me. My dad always used to tell me that there would be somebody to come up and kick my butt one of these days, and Hannah was the one to kick my butt. And a few years later, Hannah had somebody kick his butt.”

Surprisingly, all of the travel and jet setting – and jet lag – wasn’t that big of a deal to Smith. It was just something he put up with in order to pursue his dreams in the sport he loved so dearly.

“A young kid could handle all that travel,” Smith says. “It wasn’t a big deal to me. I was young and could handle going back and forth to Europe and America every week. I’m sure a guy that is 24, 25, 26, or even 30 years old would have a harder time with it. I was racing because I loved the sport. I wasn’t doing it to make a living at it. I never went into the sport to make a living. I was doing it for fun, and all of the money and that just got handed to me. So I was enjoying going back and forth for the most part.”

When all was said and done and the curtain closed on the 1976 campaign, the reviews were mixed on Smith’s overall performance. While a number of detractors felt that what he had attempted to accomplish was far too comprehensive and exhausting, Smith doesn’t really see it that way.

”I lived it and was there,” he says. “I know what it was like to fly all over the world and race the bike. Anybody that was back at Honda with their feet up on the desk or whatever, listening to what was happening and seeing all of the results, may have felt that it was too much for one person to do, but in reality, it could be done.

“I felt proud about what I accomplished, but I didn’t feel good about not winning a championship in either series. We tried to win both and didn’t win either, so that was kind of a downer. I just had to remind myself that we weren’t on as good of equipment as we could have been on. I feel confident that if I had a bike as good as the one I had in’74 and ’75, I could have won both the National and the Worid titles that year. But Honda was into making a lot of changes on that ’76 bike and it just wasn’t up to par.”

When the European Grand Prix circuit concluded, Smith packed up and hightailed it home, never again to return. In his rush to return to America, did he ever contemplate going back to avenge his run at World Championship glory?

“I’m glad I did it, but no, I hated Europe,” Smith says bluntly. “I did not like it and still don’t like it. I could care less if I ever went back there. The people were rude, the food was terrible. End of story. The whole place was strange.

“There were some nice people in the Scandinavian countries; the people were really friendly and the scenery was pretty. But the countries like France and Italy and Germany, I don’t know, it just wasn’t to my liking. The people were really into it over there. But still, being an American, tl1ey didn’t look at us like they looked at their own. Even then, we were the rebels. We were the bad guys.”

Now, 20 years later, Smith believes that Europe is a warmer place for the American riders, but that doesn’t mean that they would be able to fight for themselves in a war of two worlds.

“The caliber of riders today – these guys don’t train,” Smith claims. ”I used to ride every single day for 45 minutes to an hour, without stopping. I was in really good shape and none of the guys do that these days. Taking that into consideration, they probably would have a harder time traveling back and forth week after week.

“But now, things over in Europe are different. The food is probably more Americanized, there are more Americans going over there now, so they probably receive a warmer greeting. Back then there were only one or two Americans racing there – Jim Pomeroy and Brad Lackey – the Europeans treated me like crap back then. But these days, think it’s a lot better for the Americans. Maybe it would be easier these days.”

Is there a rider today, in the modern era of 18-wheel trucks, TV crews and personal trainers, who Smith believes could pull of the incredible feat he attempted in ’76?

“Jeremy McGrath – and I’ve always said that. He has the same attitude I did because he is racing because he loves it. I started racing because I loved it. I didn’t sit by my phone and wait for a call from Honda or Yamaha. It just happened – and I was pretty surprised when it did. That’s why he is doing so good now, because he loves the sport and it pretty much shows.”

Amazingly, in a young sport that seems to forget its past all too easily, Smith’s name is still a big deal in the world of American motocross. Based in El Cajon, California, Marty Smith stays busy teaching motocross schools and staying involved in the sport he still loves.

“The schools are doing great,” Smith says proudly. “This has been an epic month for me – a record month as far as business goes. Every year, and this has been going on for the past three years, my schools have been getting bigger and bigger, and I’m proud of that. I’m also very proud that my name is still out there.”

Read more of the Cycle News Archives here.