Rennie Scaysbrook | December 14, 2016

The 2016 Kawasaki ZX-10R hit its target of winning the WorldSBK Championship in the hands of Ulsterman, Jonathan Rea. We headed to Motorland Aragon in Spain to get speak to the champion, his team’s main players and grab some seat time on the world’s most coveted production racing motorcycle.

Lean, green, fighting machine. Jonathan Rea’s WorldSBK Kawasaki ZX-10R is an exercise in controlled aggression.

Lean, green, fighting machine. Jonathan Rea’s WorldSBK Kawasaki ZX-10R is an exercise in controlled aggression.

Photography by Kawasaki Europe, Gold & Goose

Two titles in a row for the Kawasaki ZX-10R

These are red letter days for the Kawasaki Racing Team. The 2016 season marked the third time in four years the team has ran rampant in the world’s premier production racing category, sealing the title with star rider Jonathan Rea in what would be the Ulsterman’s second straight title.

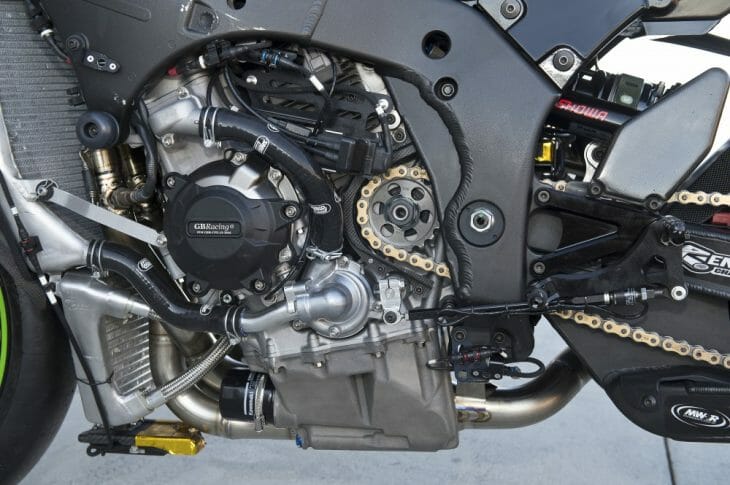

The 2016 season saw the debut of an all-new Kawasaki ZX-10R after five seasons with the previous model. It also meant a new development path with the all-new, light inertia engine, one that invariably favored Rea’s high corner speed approach over his teammate Tom Sykes’ stop-and-go style.

“The biggest difference between this and last year was the engine character – the bike required you to ride a different way,” said World Champion Rea. “So I had to quickly change my riding style to get the best out of the bike. With grip, the bike was incredible. As soon as the grip started to go our tire consumption wasn’t the best, compared to last year.”– Jonathan Rea

“The biggest difference between this and last year was the engine character – the bike required you to ride a different way,” said World Champion Rea. “So I had to quickly change my riding style to get the best out of the bike. With grip, the bike was incredible. As soon as the grip started to go our tire consumption wasn’t the best, compared to last year.”– Jonathan Rea

Rea’s chameleon riding style was thus the key to unlocking the extra speed required from the new machine in order to clinch the second title, in a season that saw nine wins and 23 podiums notched against his name.

“Next year, we have to focus with the engine. We have to make a very good product in the beginning of the year, especially about mileage in each engine. In the first year, you don’t really know the engine because you don’t know the limits. We can use new upgrade parts to have a little bit more durability and a stronger engine for racing. And then, in the same time, we will be trying to go forward with the balance of the bike and the rider” – Pere Riba, Crew Chief to Jonathan Rea

“Next year, we have to focus with the engine. We have to make a very good product in the beginning of the year, especially about mileage in each engine. In the first year, you don’t really know the engine because you don’t know the limits. We can use new upgrade parts to have a little bit more durability and a stronger engine for racing. And then, in the same time, we will be trying to go forward with the balance of the bike and the rider” – Pere Riba, Crew Chief to Jonathan Rea

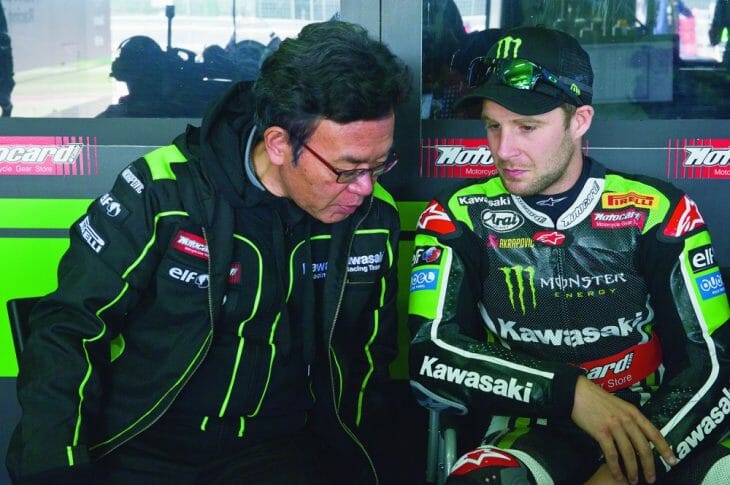

“The top riders, they are able to change a little bit their riding style depending on the character of the bike,” says Rea’s Spanish Crew Chief, Pere Riba, himself a former WorldSSP winner and WorldSBK rider. “Johnny is one of these top riders and he’s able to change, but it was important that the package of the bike was right for him. The character of the engine was new (for 2016), the chassis, everything was already good, but then he adapted the riding and the base things, and straightaway it was fantastic.”

The 2016 machine was a different animal to the trusty 2011-2015 steed. In chassis terms it was similar to the old bike, but the new engine threw the team a curve ball.

“I’m quite happy with the way things have gone. Honestly finishing second in the championship, it’s obviously not the perfect situation but I’m happy with second because Kawasaki have done a great job. We’re always learning. The good thing is in the past few years it’s been very consistent, always there to fight for the championship. Next year we need to make the step. That’s basically it in a nutshell” – Tom Sykes, 2013 WorldSBK Champion

“I’m quite happy with the way things have gone. Honestly finishing second in the championship, it’s obviously not the perfect situation but I’m happy with second because Kawasaki have done a great job. We’re always learning. The good thing is in the past few years it’s been very consistent, always there to fight for the championship. Next year we need to make the step. That’s basically it in a nutshell” – Tom Sykes, 2013 WorldSBK Champion

“The big difference was the crankshaft inertia,” says Riba. “It was much lighter. We spent five or six races trying to understand the best package for Johnny’s riding style. When we found that we start to work with the chassis.”

For any production racebike worth its salt, the base bike that you and I buy has to be exceptional. Kawasaki’s 2016 streetbike has been one such machine, but there’s not a huge amount you can do to a factory twin spar chassis (not including the fabricated swingarm) to get it to the pointy end of the championship.

Enormous weld on the left side of the Kawasaki ZX-10R frame is to stop it twisting from the chain pull. Huge radiator and oil cooler keeps things at the right temp.

Enormous weld on the left side of the Kawasaki ZX-10R frame is to stop it twisting from the chain pull. Huge radiator and oil cooler keeps things at the right temp.

“When we work on the chassis, we can work with swingarm length and the main frame head pipe,” says Riba. “We can play with the offset and the angle, but the changes are only very small, race to race. The entire bike needs to be a package: the engine works with the chassis, and they both work with the electronics.

“For example, if we say the bike has a lot of spinning, you can control this with the electronics. But if you have no mechanical grip, it’s very difficult. The electronics will control the bike but you need to find the power between the grip and the electronics and the character of the engine. It all works together.”

Factory Showa shock. Showa supplies only the Kawasaki ZX-10R in WorldSBK and thus the team only gets the best equipment.

Factory Showa shock. Showa supplies only the Kawasaki ZX-10R in WorldSBK and thus the team only gets the best equipment.

Part of the Kawasaki Racing Team’s arsenal in getting the power to the ground has came via its use of splitting the throttle bodies into two separate banks when the bike is on the side of the tire – essentially making the inline four a pair of parallel twins when the throttle is first opened up to 30 percent. This softens the power delivery, and makes the torque hit less aggressive. But for next year, this advantage will be taken away, when the new WorldSBK rules dictate the team must run the same throttle bodies (all four opening at once) as the production bike.

Rea’s electronics engineer, Paolo Marchetti, is thus the man who has had more work cut out for him than most in 2016. Marchetti is a master of the Marelli MLE electronics the team uses, and, having spent well over 15 years in the WorldSBK paddock, works closely with Rea at every race.

“Working with Jonathan is excellent because I talk with him when he’s outside the bike. He’s a fantastic, easy guy. Then he jumps on the bike and transforms himself into a monster. When he closes the visor, it’s like he becomes perfect, precise, always fast. He always put the tire in the same place. That’s typical from a champion. You can give him something and he pushes right to the limit. So we move the limit here, and he’s here. We move the limit again, and he’s here. He’s always pushing against the limit. It’s a never-ending process” – Paolo Marchetti, Jonathan Rea’s Electronic Technician

“Working with Jonathan is excellent because I talk with him when he’s outside the bike. He’s a fantastic, easy guy. Then he jumps on the bike and transforms himself into a monster. When he closes the visor, it’s like he becomes perfect, precise, always fast. He always put the tire in the same place. That’s typical from a champion. You can give him something and he pushes right to the limit. So we move the limit here, and he’s here. We move the limit again, and he’s here. He’s always pushing against the limit. It’s a never-ending process” – Paolo Marchetti, Jonathan Rea’s Electronic Technician

“Up to the end of this year, we could do whatever we wanted (with the throttle bodies),” says Marchetti, “and you can hear the bike on track (when on its side, the Kawasaki pops and burbles like the traction control is kicking in, but it’s actually the twin bank of throttle bodies as the bike uprights itself off corners). “Now we have to run a standard throttle body and we have to find a different way to try to get the same results. The main target is always the same, but power delivery must be smooth. You must save the tire for the last five laps. Now it’s much more difficult.”

Rea and the team have already found the 2017 set-up, where all four throttle bodies open together, works just fine. The team experimented with the change at Jerez and Qatar, and to the team’s relief, Rea liked the change more than what he used throughout the 2015 and 2016 season.

Mission control for the factory Kawasaki ZX-10R. Magneti Marelli MLE dash tells the rider all he needs to know. Right switches include kill (red) traction control (white) and start (yellow). Left switches are: map (white, top), scroll up menu (red) and down (blue). Bottom white is pitlane speed switch.

Mission control for the factory Kawasaki ZX-10R. Magneti Marelli MLE dash tells the rider all he needs to know. Right switches include kill (red) traction control (white) and start (yellow). Left switches are: map (white, top), scroll up menu (red) and down (blue). Bottom white is pitlane speed switch.

“Johnny is a bit of an old style rider,” says Marchetti. “He likes control in his wrist. Before he was complaining sometimes that the bike was doing too much for him. Now he’s got much more in his hand.”

Another area Marchetti is constantly working on the Kawasaki ZX-10R with Rea is the electronic engine braking maps.

“Jonny is obsessed with the engine brake,” says Marchetti. “He carries a lot of corner speed, but to think of engine braking as more or less is a bit too simplistic. It’s a matter of how much you want, but you must think, for example, when he brakes into the corner, you have to follow the rear tire slip from this point to this point (Marchetti gestures with his hands to signal different points in the corner).

And you have to say, ‘okay, I want this, this, this engine brake… all the way through the corner’. On one corner, you can find the perfect set up. You can even find the perfect set up all around the circuit, but then it’s a race and Johnny’s fighting the other riders; he’s braking harder and deeper, he’s using a different gear or changing gear at a different point or he’s on a different line. So for him, it’s very important to have the right amount of negative slip. The right amount in every second, in every angle, he’s going into the corner. And this is to follow the tire grip.”

“In racing, Showa supplies only Kawasaki. Showa brings many, many new parts for each race. We sometimes compare with Öhlins, so we know in one area Showa is better, another area Ohlins is better, but the comparison with Showa is tight. For the production model, Kawasaki chose Showa. We are happy with Showa. From the chassis point of view, the difference between 2015 and this year’s ZX-10R is just the swingarm pivot – 3mm lower for this year. This is normal for the street rider – this lower pivot creates more movement of the rear shock, and the rider feels a little bit more comfortable – it’s not such a harsh feeling. The production engineers are going to this direction, but this is not suitable for a racing bike. So we go 3mm back up” – Ichiro Yoda, Kawasaki Racing Team Senior Engineer

“In racing, Showa supplies only Kawasaki. Showa brings many, many new parts for each race. We sometimes compare with Öhlins, so we know in one area Showa is better, another area Ohlins is better, but the comparison with Showa is tight. For the production model, Kawasaki chose Showa. We are happy with Showa. From the chassis point of view, the difference between 2015 and this year’s ZX-10R is just the swingarm pivot – 3mm lower for this year. This is normal for the street rider – this lower pivot creates more movement of the rear shock, and the rider feels a little bit more comfortable – it’s not such a harsh feeling. The production engineers are going to this direction, but this is not suitable for a racing bike. So we go 3mm back up” – Ichiro Yoda, Kawasaki Racing Team Senior Engineer

Does the system learn the tire grip is going down and then adapts?

“It’s a bit smarter than that,” says Marchetti. “There’s no point in having the system learn what you want in one corner for the next lap, because then you are a lap too late. You needed this adjustment the lap before. So the system is reacting in real time. It’s reacting to what is happening. Our challenge is to write the strategy that makes this thinking in real time. The system must think, ‘This is happening now so now I have to do this. This is happening now, or this is not happening anymore, let’s put it to a second later because it’s deeper into the corner and a different lean angle, with more or less engine brake.’ There’s no GPS, because GPS is not accurate enough. It’s all a big headache.”

“You must always find a balance, because in the end, most of these bikes are riding over the limit. You need to have a very nice machine for people who use it on the road but you also want to have a competitive bike on the racetrack. Kawasaki has probably one of the best machines on the road, and we were able to win a championship in the last couple of years. So Kawasaki did a really good job” – Marcel Duinker, Crew Chief to Rea’s teammate, Tom Sykes

“You must always find a balance, because in the end, most of these bikes are riding over the limit. You need to have a very nice machine for people who use it on the road but you also want to have a competitive bike on the racetrack. Kawasaki has probably one of the best machines on the road, and we were able to win a championship in the last couple of years. So Kawasaki did a really good job” – Marcel Duinker, Crew Chief to Rea’s teammate, Tom Sykes

Headache or not, the combination of Rea’s brilliance, Marchetti’s know-how, and Riba’s understanding from a rider’s point of view has made the Kawasaki Racing Team the ones to not only beat but aim for in the World Superbike Championship. Ducati is clearly coming on strong, as Chaz Davies has shown in the latter part of the 2016 season, and KRT will once again have to up their game if they are to take a fourth title in five years in 2017, but rise to the challenge is what champions and champion teams do.

Riding the fastest Kawasaki ZX-10R on the planet

The Jonathan Rea Kawasaki ZX-10R’s handling is spot on, as you’d expect from such a bike.

The Jonathan Rea Kawasaki ZX-10R’s handling is spot on, as you’d expect from such a bike.

I’ll cut right to the chase with my impression of Jonathan Rea’s World Superbike title winning machine.

This machine is utterly, stupendously, awesome.

But you knew I was going to say that, right?

How could it not be? This is a bike fit for a king – it’s set up by the very best technicians in the game, comes with the full backing of one of the biggest motorcycle and heavy industries companies in the world, and has access to parts we can only dream of.

Riding the factory Kawasaki ZX-10R is easy. To a point. At my pace, the 10R is smooth, fluid and graceful. At Rea’s pace, it mightn’t be as friendly. But I’ll never know.

Rea likes his bars set quite wide, a bit like a motocrosser, thanks to his background of sending it over triples and whoops in Northern Ireland. It’s a roomy cockpit, even for me, as I’m about half a foot taller than Rea.

The team fires the bike and I’m off down pitlane, no sooner than 10 seconds after sitting on it. I’ve been racing a ZX-10R in Southern California but this thing feels wider thanks to the fairing that protrudes out to the side further, and the Marelli MLE dash looks like a spaceship interface compared to a standard ZX-10R.

Those forks may look similar to a standard Kawasaki ZX-10R’s but they don’t feel like it! No carbon brakes like in MotoGP. And no, you can’t have those Brembos.

Those forks may look similar to a standard Kawasaki ZX-10R’s but they don’t feel like it! No carbon brakes like in MotoGP. And no, you can’t have those Brembos.

Two things standout for me. This first is how easy this bike is to maneuver between the right/left of the Reverse Corkscrew at the back of the Aragon circuit, and the long, long left that follows, and the braking stability. Rea’s bike is so light and nimble in direction changes that I barely need to look where I’m going and it takes me there. The ride is also nowhere near as stiff as I thought it would be. The suspension is rather plush, certainly softer than my production racer, and this comes as a surprise.

Under heavy braking the factory four-piston, radially-mounted Monobloc Brembos have exceptional feel and power and the ZX-10R’s front end loads up effortlessly and gets the job of turning done with the minimum of fuss, and is a testament to just how good the factory Showa suspension is on Rea’s racer. The suspension has such a quality feel and is so, so far in front of what you or I can get on a standard ZX-10R that two are incomparable.

On rails. The bike, not Rennie! Our Road Test Editor came away extremely impressed.

On rails. The bike, not Rennie! Our Road Test Editor came away extremely impressed.

The second standout point for me is, you guessed it, that engine. I’ve no doubt this is the fastest racebike I’ve ever ridden, and I’d be shocked if this thing had any less than 220-230hp at the rear wheel (the team won’t say what it’s got, unsurprisingly). The power comes in so smoothly when cornering thanks to the split throttle bodies, the Kawasaki burbling on its side like the traction control is operating at its maximum, but forward drive is totally uninhibited. The engine almost feels like something I could easily ride to the shops on, not a world title winning factory motor, until you give it anything more than about 20 percent throttle. Then, hold on.

Down the back straight, I let rip on the factory ZX-10R. The anti-wheelie kicks in and floats the front end, and it’s game on. My. God. This thing is so, so fast. Any notions of the bike being one for amateurs is quickly dashed as my peripheral vision liquefies in a guttural scream of factory four-cylinder superbike at full tilt.

Even with no clothes, the factory Kawasaki ZX-10R looks achingly fast.

Even with no clothes, the factory Kawasaki ZX-10R looks achingly fast.

It is one of the most glorious sounds I’ve ever heard.

The electronics work so fluidly that it’s hard to notice they are there at all. I can’t tell you or not if I got the traction control working because I must admit to riding conservatively due to the fact I really had no idea where I was going, having only done four previous laps of Motorland Aragon on a ZX-10RR. That’s got nothing to do with the bike. It throws waves of confidence inspiring feel at the rider even at my pace – I wish I rode the bike at somewhere like Valencia as I know my way around there much better and would be more comfortable in really pushing it, but, hey, beggars can’t be choosers!

The anti-wheelie is impressive, and allows the bike to hover the front end just enough that the rear tire loads up fully and drive it as explosive as possible. The whole experience of riding the WorldSBK Champion’s machine is all consuming, and over all too early.

Rea’s mechanic Oriol Pallarès has a slightly concerned look on his face, knowing he’s about to entrust his baby to Rennie!

Rea’s mechanic Oriol Pallarès has a slightly concerned look on his face, knowing he’s about to entrust his baby to Rennie!

Four laps are done, and I’m back in pit lane.

I rode this bike at nowhere near Jonathan Rea’s pace. But that’s OK, because riding the champ’s bike gave me an insight into a world I wish I had the skills to fully exploit, but am unable to do for two reasons. One, if I crashed I’d be found in a Spanish torture chamber somewhere and two, I’m not of Mr Rea’s skill.

But it also gave me, and you, a look into a group of individuals operating at the top of their game, and really impressed upon me the team aspect of motorcycle racing.

What an experience.

The real star of the Kawasaki ZX-10R show, 2015 and 2016 World Superbike Champion, Jonathan Rea. To read our full chat with Rea, taken at Motorland Aragon, click here.

The real star of the Kawasaki ZX-10R show, 2015 and 2016 World Superbike Champion, Jonathan Rea. To read our full chat with Rea, taken at Motorland Aragon, click here.